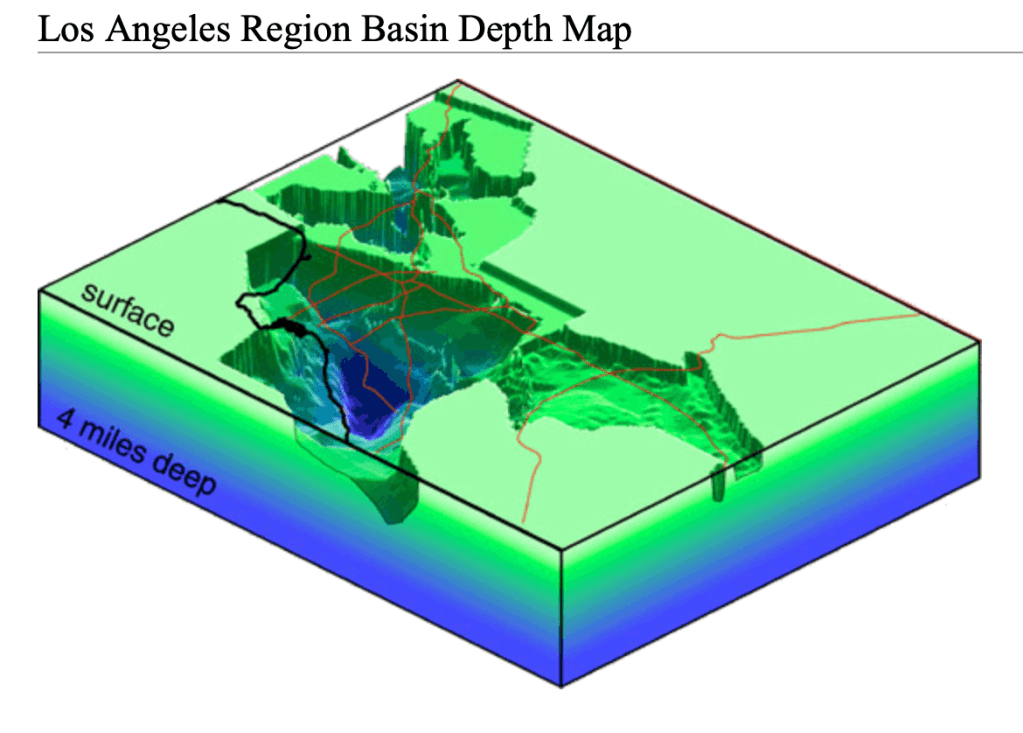

It turns out if you vacuumed up the loose soil, rocks, people, buildings, fossil fuels, and cars from around the LA area, a four mile hole would remain. If you happened to be walking past The Los Angeles Coliseum when all this loose detritus magically vanished, it would take about ninety seconds to free-fall to the bottom. While plunging to your lonely death, there would be plenty of time to admire the vertical cliff faces of the the North American and the Pacific Plate. Let’s take the dive into the rabbit hole of LA’s seismic past and present.

We all kinda understand plate tectonics. The Earth is mostly composed of this hot, gooey rock which undulates beneath our feet. Even though the planet is blanketed by a warm layer of air, Earth still radiates heat into space. Space, the final frontier, is alarmingly cold. So all the gooey rock freezes at the surface. Hence, the crust we live on. If you’ve ever baked brownies, you can see the same basic principle at work. Heated from below, a thin, relatively cooler crust forms on top while the warmer, chocolate goodness remains liquid beneath. As the underbaked middle continues to cook, the delicious concoction of chocolate, flour, egg, and sugar moves around creating breaks on the thin crust above. Voila! You have witnessed a fault line forming. Earth science is delicious!

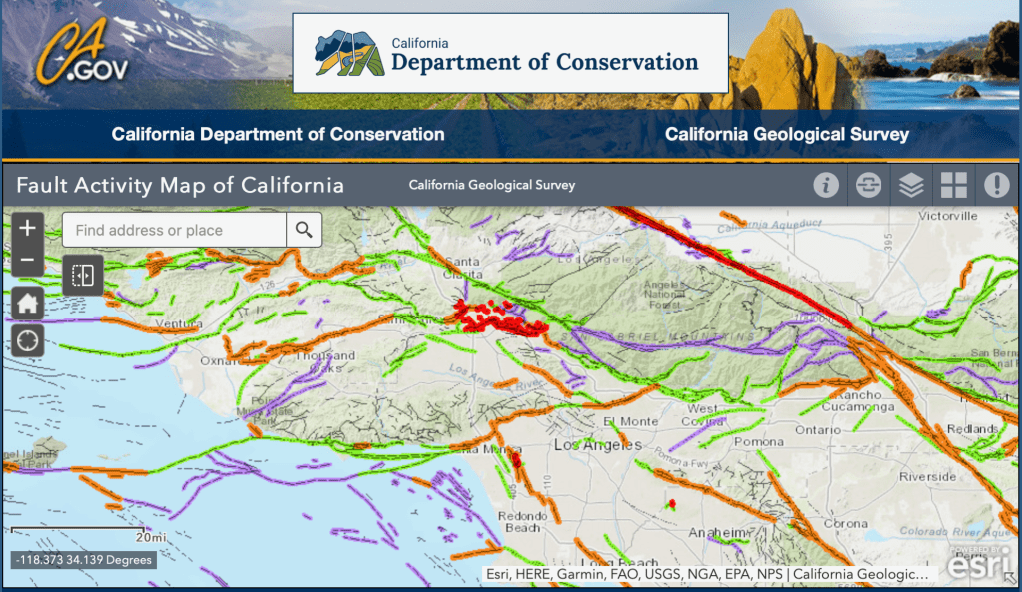

Faults and frays are where plates meet, and they’re just breaks in the crust. There are many throughout the LA region. If the planet were older or the core cooler, a thicker section of the surface would be frozen solid. There might not be any breaks in the crust at all, meaning no volcanoes, earthquakes, or stunning mountain ranges. That’s just not how things worked out for Earth. Our home is mostly gooey hot rock, likely left over from when a Mars sized planet smashed into proto-earth early in the solar system’s life. If the Earth were the size of a basketball, our cold, habitable crust would be the thickness of a sheet of paper. We’re actually lucky there’s enough of a crust to live on at all because, frankly, there almost isn’t.

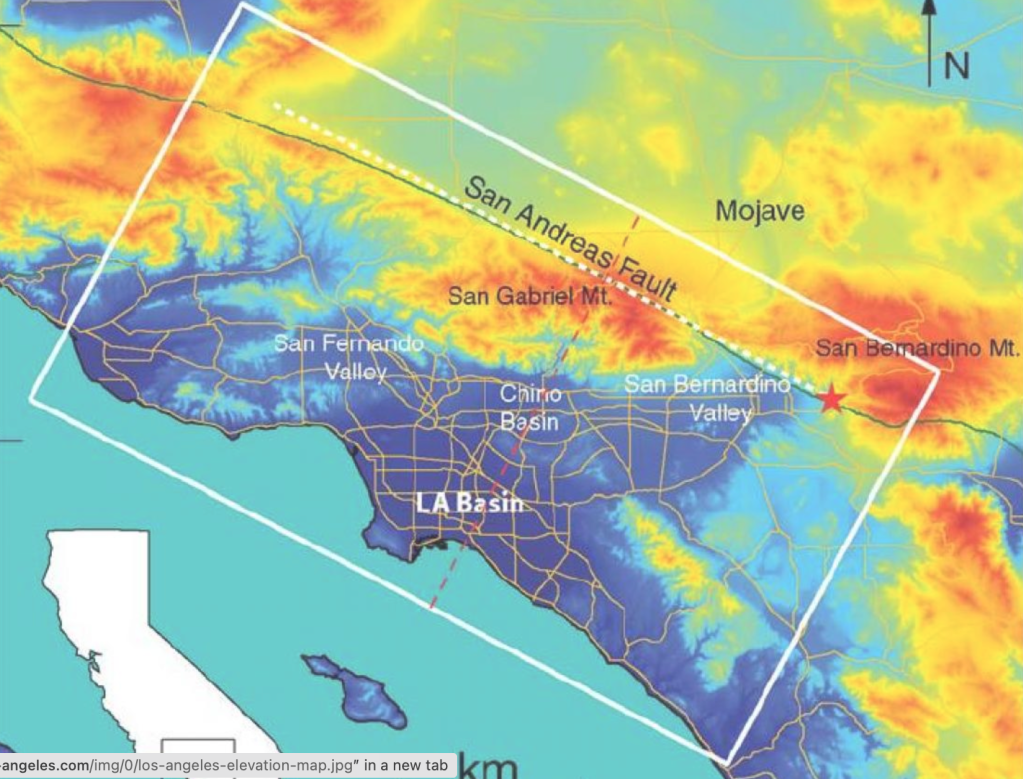

We all sorta know exciting things happen at plate boundaries. We also know LA sits near one of these boundaries, the San Andreas Fault. It actually runs well east of the city, but let’s save the technicalities for inconsequential marital disagreements. LA sits mostly on the Pacific plate, which is smashing into the North American plate at an average rate of super duper slow. That’s an average. In real life, the rate isn’t uniform. Sometimes the plates lock and build up stress, the release of which has … moving … consequences.

Our two plates are grinding by each other with all the grace and smoothness of two Trisket crackers, where one weighs about 3,207,000,000,000,000,000,000 pounds (water is heavy) and the other weighs considerably less (dirt is not). Their interface is not cordial. Chunks of each plate are sheared off, pushed up, or rotated as the Pacific Plate sinks below the North American Plate. It’s ugly. This is how our four mile hole starts forming bazillions of years ago.

Nature abhors a vacuum. The hole, which starts out as just a shallow depression, fills with warm ocean waters. Life flourishes in the shallow sea. As time passes, dead organic matter settles to the bottom. This goes on for millions of years. Slowly the plates move and twist, slowly the hole gets bigger, slowly the hole fills with more and more dead creatures and sediment. The organic matter at the bottom gets compressed as weight is added on top. Eventually the pressure rearranges the actual carbon atoms and wonderful, consequence-free fossil fuels are created. The LA we know today exists because of these processes.

It is a myth LA or California will fall into the sea. Makes for good TV, though. I think a degree of schadenfreude is at play, too. LA has such nice weather and beautiful scenery, it is inconceivable to us that in a fair and just universe something disastrous won’t soon occur. Danger does exist. Like Mexico City and Christchurch, New Zealand, much of the city sits, not on solid ground, but on a loose amalgamation of small rocks, sand, soil, and long dead things. Remember, bedrock is miles away. This poses dangers for structures during earthquakes.

Buildings resonate, not unlike a tuning fork, but at much slower frequencies. They sway. Short buildings might resonate every second or two, meaning it takes that amount of time for energy from the ground to travel up and back down the building. Skyscrapers take longer, maybe 5 to 12 seconds. All this depends on a variety of factors, like building material and construction techniques. Software exists to calculate this.

So the buildings and ground move at particular periods or frequencies depending on an enormous list of variables. Should these frequencies be similar, confluence occurs. Two (or more) waves arrive at the same time and amplify each other. More energy means greater damage. If the ground and building movement are not synced up, interference occurs. Thus, the resulting energy is diminished. Less energy, less movement, less damage.

Building major cities on loose infill was not a great idea. Unfortunately nobody understood the far-off consequences and it’s too late to move everything. In the LA Basin seismic waves bounce off the bedrock and through the infill like water in a … basin. The harder the hit, the more violent the “water” sloshes back and forth. The resulting damage from major earthquakes in these areas can be extreme and frustratingly random, as happened in Mexico City in 1985 and Christchurch in 2010 and 2011. Some blocks are spared, while others are leveled. Humans adapt though. New construction techniques are being researched all the time. Still, designing a structure to withstand a magnitude 7 or greater earthquake might never be economical or feasible. Additionally, fully understanding all the forces occurring on a structure built in these type areas during earthquakes might never be possible.

The LA basin is approximately 50 miles long and 25 miles wide. It covers an area roughly 1,000 square miles. The western boundary is The Pacific Ocean and Santa Monica Mountains. The San Gabriel Mountains demarcate the eastern boundary, to the north, the Santa Susana Mountains, and to the south, the Puente Hills and Palos Verdes Peninsula.

LA will never fall into the ocean, it’s actually rising up. Tectonic forces are a fact of life. About 10,000 tremors occur each year, though only about 20 are noticeable. For now, The Big One, whatever that means, has yet to materialize. Hopefully we will all be long gone if or when it does.

For me, that means … like … day after tomorrow. Surely the Triskets can hold till then.

You must be logged in to post a comment.