I first learned about the Okavango delta in a documentary called Planet Earth. It aired in 2007 in the U.S. The first episode, Pole to Pole, did a segment on the Delta. I was immediately entranced.

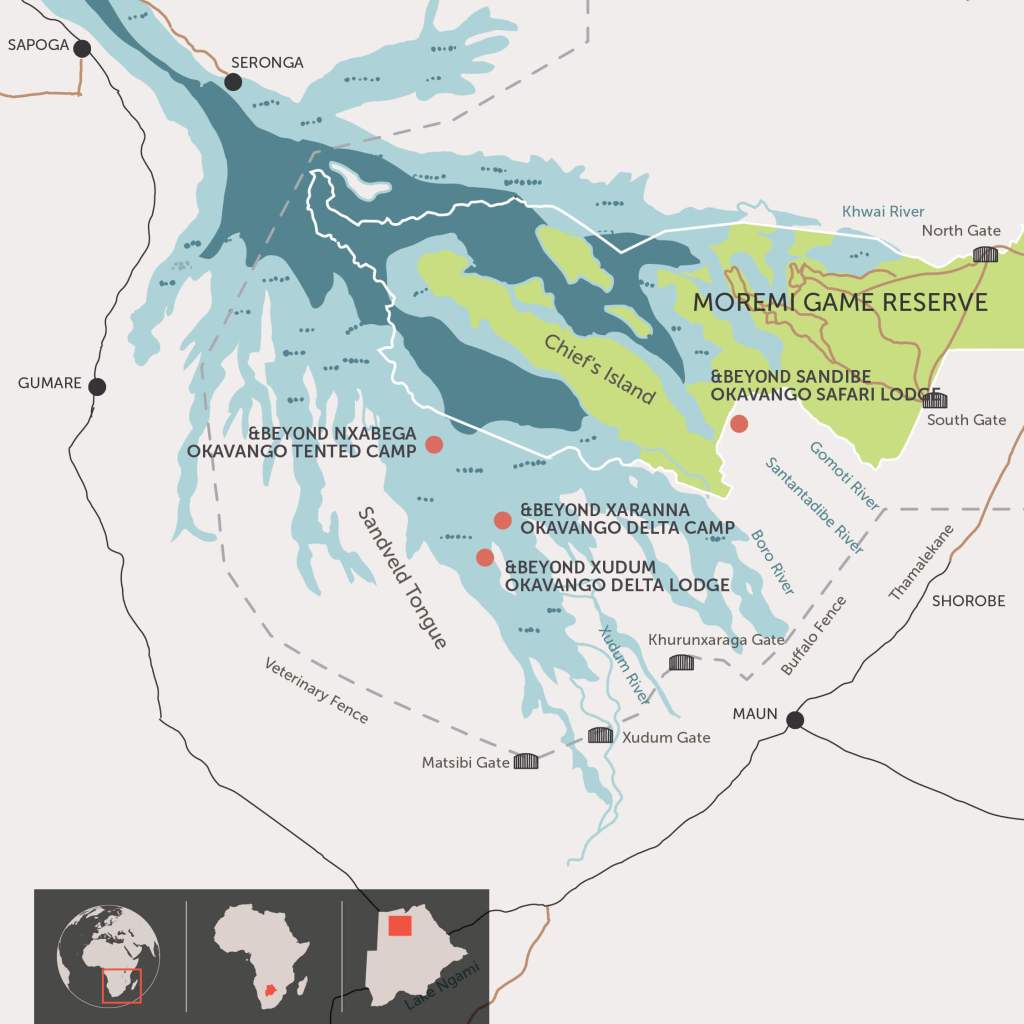

Fifteen years later here we are at a tented camp called Nxabega. It’s a tent, yes, but please don’t think we’re roughing it. We are light years beyond my camping experiences in the woods of South Carolina while in Boy Scouts. Those tents had no bar, king bed, outdoor shower, indoor shower, deck overlooking the delta, or really anything that could be remotely categorized as a human comfort.

Returning to our metaphor where I am an alien “from Germany,” why come here? As my mom said to me, “Isn’t it the same animals you already saw?”

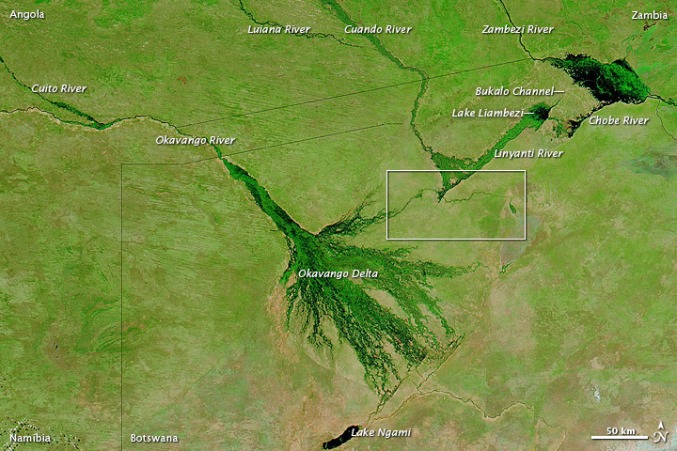

Most deltas, like the Mississippi River delta, come from large rivers that fan out as they approach the sea. Here it’s different. The water you see begins thousands of miles away as rain in Angola, to the north of Botswana. Moist sea air hits the mountains and condenses as it is pushed upward by the topography. This heavy, cool air falls as rain back to the ground. It takes 5 to 6 months for that water to flow down to Botswana, into what is known as an inland delta. This delta, unlike every other delta on Earth, does not flow into a sea or ocean. It is unique in all our planet. Plate tectonics are to blame, which makes this microclimate a temporary blip in the totality of Earth’s history. One day, the plates will shift and all this will end.

The delta is fed by the Okavango River, the 4th longest in Africa. As it flows into this basin, which ranges from between 3,000 to 5,000 square miles, or roughly the size of Connecticut, it flattens and spreads. Most of the water evaporates.

Botswana is a semi-desert, as rain does fall in the warmer months but sporadically. Thanks to the Angolan rains, this area becomes an oasis for thirsty animals in the dry, winter months, which is why they are here in such high concentrations. It also explains why I am here, really, why any of us are here.

The animals are pushed together by a need for water, all but ensuring visitors see animals interacting with other species and their own. I think that’s what makes this area special. Anyone can see a lion, just go to a zoo. Here you can see a lion interacting with its mates, as they care for their cubs, as he protects his pride against intruder lions, who, given the chance, would kill his cubs and take his territory. Here you can see a leopard stalking warthogs and impala. Here you can witness how life moves in a place without fencing. It is brutal and beautiful at the same time.

All thanks to a quirk of geology.

You must be logged in to post a comment.