I did a lot of research about the geological history of the Appalachian Mountains. It’s long, involves lots of dates and eras, all of which involved too much writing and research. So instead, I’ll tell you the highlights. It occurs to me people might not be as interested in rocks as I am.

It all starts about a billion years ago. For the record, that’s a long time. If you were able to travel back in time one year per second, it would take you about an hour to witness Jesus’s birth. (Give the wise men my regards.) It would take an additional 31 and a half years to reach the birth of the Appalachian Mountains. Along the way, you’d see the dinosaurs come and go (well, since you’re going backwards they’d go and come.)

It all begins with a supercontinent, Rodinia. After a few hundred million years, it slowly breaks apart, as all supercontinents do. A shallow sea forms, called the The Iapetus Ocean. Then, as tectonic plates “often” do, one or both change direction. The Iapetus plate reverses and smashes into the proto-North American plate. Uplift and heavy volcanic activity result as one plate slides underneath another.

Pangea forms and the new Appalachian Mountains rise from the sea. These equatorial peaks dominate the surroundings, reaching as high or higher than the Himalayas today. Massive rain forests cover the land. One day, humans will mine and burn coal, which is created by all this long dead organic matter.

Then, as all supercontinents do after a hundred million years or so, it breaks apart. The Appalachian Mountains begin to erode, but before too “long” the plates change direction and boom, uplift again. More rocks get pushed up and folded. Then apart. Then together. This cycle continues for “awhile.”

“Eventually” the African plate and the North American plate part ways. The Atlantic Ocean is created and continues to grow in size today.

Tectonic plates move about as fast as your finger nails grow, which blows me away every time I cut my nails. The Appalachian Mountains begin eroding again, resulting in the nubs we see today. Well, technically geologists call them cores … the frozen magma interiors of mountains after all the loose rock and top soil has eroded away.

Years ago RBD and I hiked up Grandfather Mountain, which is an all day affair requiring enormous effort. I am unclear to this day how we survived. Near the top were massive slabs of rock pushed vertical, creating enormous rock faces. Embedded in the rock were tiny sea creatures, more than a mile above and hundreds of miles away from the nearest ocean. It’s not something you expect to find up there.

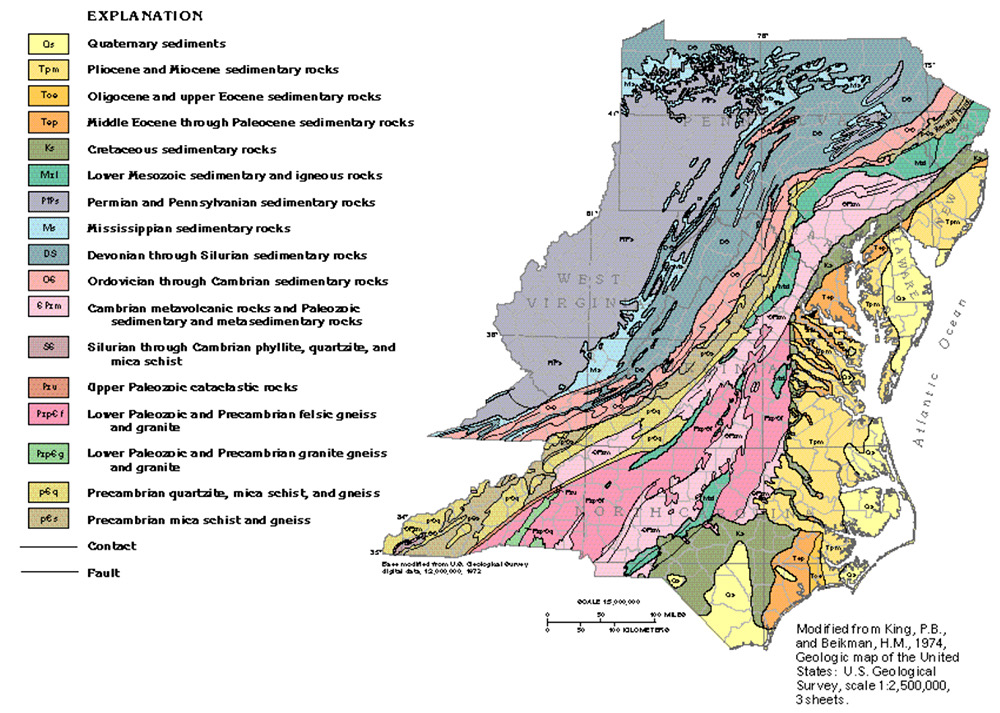

The Appalachian Mountains are surprisingly diverse geologically. They grew and shrank and grew again over 1,000 million years. On one ridge, rocks at the tops may be a billion years old. However, the next ridge over might have rocks from a different uplift period and be hundreds of millions of years younger. Rivers came and went as mountains grew and shrank, cutting deep gorges (like Linville Gorge) and creating caverns (like Linville Caverns), both of which are an easy drive from Blowing Rock.

The Rockies and Himalayas are pretty. They’re young, sexy, tall, and look impressive from a distance. Plus, with all that snow on top, you know they’re dressed to impress.

Despite all that, my heart belongs here, to The Appalachian Mountains. I mean, sure they’re old, small, and craggy. But being here gives you access to a truly ancient landscape and helps (me, at least) appreciate just how deep time goes.

These small mountain streams and springs have flowed for an almost incomprehensible amount of time. Wind has swept these peaks for not one, two, or even three but several epochs. Entire species have evolved, lived, and died while the Appalachian Mountains watched. To them, all our history is but .004% of their history.

For all humanity’s pomp and circumstance, we are but a blip in a long story. My time here is even less significant. Knowing my place in the order of things keeps me grounded.

You must be logged in to post a comment.