I am home now. Before parting ways for 2019, I wanted to show unique pictures of a bomb shelter I toured in Clapham South.

Most everyone has seen the photos of Londoners sheltering in tube station. This only worked so well during the Blitz of 1941 and 1942. Some stations were built using a cut-and-cover method, which meant they weren’t all that deep. Bombs would fall nearby, rupturing water and sewage lines, and people would drown. Deep stations, too, were not immune from inundation and the panic causes. Another, safer solution was needed.

The government began building the deep shelters along the Central and Northern lines in 1941, and concluded a year later, about the time the Blitz ended. The idea was to use the tunnels as express stations and train tunnels after the war, hence their proximity to existing London Underground infrastructure.

Later in the war, Germany began bombing London again. This time the shelters were ready and open for business. People had to haul their own bedding up and down every night. However, if your house had been destroyed, you could leave your bedding and some belongings permanently. People continued living there after the war while their homes were rebuilt.

Each shelter held 8,000 people. A medical bay and doctor provided free health care. This predates England’s N.H.S. and thus served to entice people to come down, since they could receive a free check-up. Shelters also had a commisarry and entertainment room. Dances and socials occurred frequently to pass the time.

After the war England had zero money to build new infrastructure; it had to rebuild so much else. The express train service never happened. Instead the shelters served as cheap hotels or barracks for military units. They reduced capacity by half to make it feel less cramped.

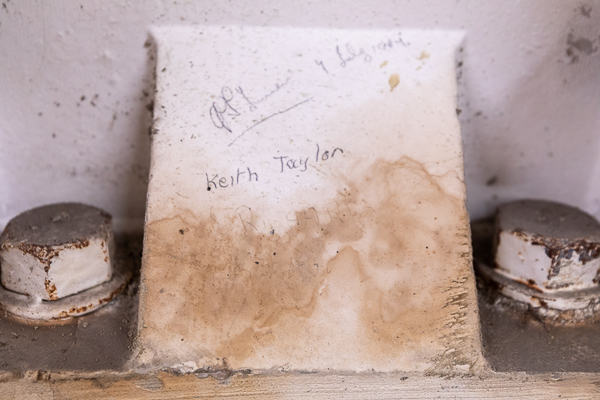

This went on till about 1957. Visitors often wrote messages on the walls, many of which are still legible. A U.S. soldier staying at a nearby shelter was burning his name on the ceiling with a lighter when a piece of paint caught fire and fell onto bedding. The fire spread quickly, destroying everything. Nobody died, but the government realized how dangerous for civilians these shelters could be. They were immediately shut down.

For decades the deep shelters were used as archival storage for the government or businesses. Eventually the government didn’t want them anymore. One shelter was sold to a farmer, who grows food hydroponically and sells it in posh London grocery stores. Others were sold to The London Transport Museum. They are now tasked with preserving and restoring the shelters. The museum has big plans, and through selling tickets is raising money to increase access (currently you have to climb twenty stories down and up) and further restore these relics of World War II. I cannot recommend visiting them enough.

This concludes our journey. Thank you all for coming along this year. It’s been an adventure! We began in Taormina for the holidays and new year, a Spring fling to Costa Rica where RBD and I celebrated ten years of matrimony, then we visited Latvia with mom to dig into our family’s ancestry, and concluded with environs around Central London. RBD and I do a family budget summit in early January. In one of the sessions, we plan all travel for that year. Thus I’m not sure what 2020 holds yet. The only thing on the calendar is Africa. We depart November 7th and return November 22nd. I plan to write and photograph about the experience, but am unsure about WiFi availability.

I head back to the airport tomorrow and fly to Charlotte. After saving for many years, we bought a log cabin home in Blowing Rock, North Carolina, about a ninety minute drive from the airport. We close on Friday, November 1st. Our plan is to make it into a vacation rental property, to help us along the road to retirement. It rapidly approaches, faster than I thought possible. I am traveling back and forth a lot for inspections and meetings. I don’t mind. As I often quip, I could use the miles. (This is actually never true.)

If you want a place to stay in the Appalachian Mountains let me know! I should provide a discount code as a thank you for subscribing to these posts. (RBD will have to approve first, though. She’s the boss.)

As I mentioned prior, if you’d like an electronic copy of any picture, or ones I will post on Facebook in the coming days, shoot me an email.

Have a lovely holiday season. Again, thank you, for reading and your notes back to me. I appreciate your time and interest. I look forward to our next trip together. Till then, be well.

You must be logged in to post a comment.