Mt Etna dominates life here. The locals refer to the volcano as a she. I find it odd assigning a gender to a volcano. Furthermore, a volcano in my opinion has more masculine characteristics. Most women in my life don’t spew fiery gases and viciously erupt, killing scores of people. That said, I don’t know any Sicilian women.

Why do people live here? Americans are quick to point out the folly of living near a continuously active volcano. Like, how can anybody be that stupid? Don’t they know the dangers? People are people, and Sicilians are not dumber or smarter than anybody else. They stay here for good reasons. So what are they?

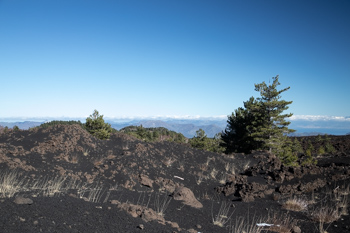

We took a tour of Etna yesterday. We hired a guide to take the four of us up and show us around. We met our guide, Salvo, in Taormina and drove to Mt Etna Park, a nature preserve where nobody is allowed to build…anymore. Buried remains of buildings, eternally encased in frozen lava flows, dot the landscape. An ominous sign.

To Sicilians, Mt Etna is a daily part of their lives. They wonder about her. Discuss her mood. Talk about what she’s been up to. Talk about her plans for the future. Etna stays on the minds of a lot of people, and has been for hundreds of years.

Unlike Vesuvius, Etna has continually erupted since people inhabited the island. By “eruption,” we’re not taking fire and explosive gases, death-from-above-type thing. Mostly she just puffs away, letting off steam 24 hours a day. From the Sicilians’ perspective, they prefer this. A volcano that erupts a little all the time is infinitely better than a quiet volcano that erupts all at once, see Vesuvius or Mt. St. Helens.

Occasionally, she does really erupt, sending lava bombs miles away and oozing copious amounts of lava. These events can destroy entire villages. One such eruption lasted for over a year. So, why do people stay?

Well, Etna has given this area of Sicily a lot. Her soil is incredibly fertile, chocked full of minerals and goodies plants love. Etna acts as a massive fertilizer factory.

She also provides abundant building materials and has for thousands of years. Most of the buildings here are built with volcanic rock. Craftsman (then and now) shape the rock into large blocks, or piece them together to create an interlocking wall. No concrete needed. Now, Sicilians use the rock as an ingredient in paving roads. Salvo noted, ironically, how the park had the best roads in Sicily because the material used to build them was close by. He wasn’t much of a fan of the government.

On top of Etna it snows. Before refrigeration, the (then) abundant snow was used to create ice, which meant merchants could keep fish fresh longer and help people avoid heat stroke during the hot, humid summers. Volcanic ash acts as a strong insulator, so merchants shipped blocks of ice packed in ash up and down the shore. An entire ice industry developed, all because of Etna.

Today Etna’s slopes provide recreation for tourists and locals alike. Snowboarding and skiing are big. Scientists monitor every inch of her, contributing to the science of vulcanology. Snow melt brings water to crops, like olive trees, lemon trees, and pistachio trees. These crops create limoncello, olive oil, pistachio wine (and nuts), and even almond wine, an intensely sweet liquor — products of Sicily we know and love. Products they export, products that help their small village economy. Etna’s porous soil cools melt water and rain as it seeps into the ocean, making the ocean temperature considerably lower in this specific area and a welcomed relief in summer. People don’t live here in spite of Etna; they live here because of Etna.

This part of Sicily owes even its existence to Etna. Otherwise, Sicily would have a large bay here and look totally different. Cities like Catania and Siracusa would be underwater (though Taormina would not since it belongs to a different mountain chain).

Etna was kind to us during our trip. She puffed as usual, but otherwise showed no signs of annoyance at our presence. Quite a contrast from Monday, when a fissure opened up on the side and spewed lava for several days. This is called a lateral eruption, and is among the more dangerous variety because it rarely gives any warning. We saw the newly formed fissure, now an impressive gash on her side below the summit. Some of the towns we drove through on our way to Etna experienced minor earthquake damage.

We left our jeeps and walked briefly to a dormant crater, while getting an excellent view of the summit.

I am caught between wanting to see Etna erupt and not wanting to be an asshole. An eruption surely means damage and consternation for others. Never good. Watching and listening to her erupt on Monday, though, and I find myself wanting more.

Ruins are nice, but geology and Mother Nature have always appealed to me much more. I couldn’t care less about which columns are Doric and which temples glorify which Gods. It all gets mixed up in my head.

But plate tectonics? Fascinating. I could stare at Etna all day and never get bored — waiting, studying, admiring her eerie beauty from our terrace. Maybe if I did it long enough, I would learn to see her like a Sicilian does.

We fear what we don’t understand. The Sicilians understand Etna, in their own way. Perhaps it’s denial, perhaps not, but in understanding her they do not fear living here. They understand the benefits granted to them come with a cost. But everything comes with a cost, doesn’t it? The Sicilians just know the price, and it gives them a confidence and bluster to live life fully.

You must be logged in to post a comment.